The 6th Battalion - Connaught Rangers

The 6th Battalion

Connaught Rangers

& Rowland Feilding

Willie Shaughnessy was in the 6th Battalion of the Connaught Rangers.

For the greater part of the Great War, the 6th Battalion was led by Rowland Feilding.

The following are extracts depicting the life of this Irish Battalion.

The first is where he describes the trench raid in which Willie was killed, the Battle of Messines and then going into what was formerly no man's land, and finding the body of WillieShaughnessy:

June 8, 1917 (Rossignol Wood)

At

10.30 on the night of June 4 I launched my raid with 250 officers and men under Captain Tuite. The objective was the third line of the enemy's trenches, in Wytschaete Wood. Tuite was to advance behind a creeping artillery barrage and was given twelve

minutes to reach his final objective. The guns were then to form a 'box' barrage till the raiders got home again. He was allowed forty-five minutes in which to do the whole business. In such active times it was not possible to interfere with the ordinary work

of the artillery for longer than this.

The raid was skilfully led and was entirely successful. These affairs sometimes seem to go off better when done on the spur of the moment than after long fussy preparation. About sixty Germans were killed and seven prisoners were brought back, including an acting officer wearing the iron cross. The raiders returned in rags, their clothing torn to shreds by the enemy's wire, and today, after four more days of fighting, their clothes are in no better condition, as you can imagine. We lost three officers - two killed and one blinded for life, I am afraid, by a bullet which penetrated his eye. There were about forty casualties among the men, mostly slight. ... One of the three principal shelters 'Harley House' - the one in which I had received my shaking two days before, was however, flattened and Murphy - one of the regimental police who was on sentry duty - was killed... Poor Murphy had a hotograph of his children in his pocket - a delightful-looking family. After midnight (June 5-6) we were relieved from the actual front line by the 6th Royal Irish Regiment.... During the night a lance-corporal of mine, who had been reported missing on the night of the raid - Fielding by name - was found in Noman's land, by another regiment and brought in. He had been lying there twenty-four hours with six wounds! His finders were greatly impressed by his stoic behaviour. The 6th Connaught Rangers were to be broken up for the battle in order to provide “mopping up” and carrying parties for the attacking battalions... I moved to my Battle Headquarters - a deep mined dug-out in Rossignol Wood, above which I am now writing this letter. The wood reeked of gas shells, to which the enemy further contributed during the night. Yesterday morning (the great day) I got up and went out at three o’clock. The exact moment of the assault (known by us as “Zero”; by the French as “l’heure H”) which had been withheld by the Higher Command, as is usual, till as late as possible, and had been disclosed to us as 3.10 am. I climbed onto the bank of the communication trench, known as Rossignol Avenue, and waited. Dawn had not yet broken. The night was very still. Our artillery was lobbing over an occasional shell; the enemy - oblivious of the doom descending upon him - was leisurely putting back gas shells, which burst in and around my wood with little dull pops, adding to the smell but doing no injury. The minute hand of my watch crept on to the fatal moment. Then followed a “tableau” so sudden and dramatic that I cannot hope to describe it. Out of the silence and the darkness, along the front, twenty mines - some of them having waited two years and more for this occasion - containing hundred of tons of high explosive, almost simultaneously, and with a roar to wake the dead, burst into the sky in great sheets of flame, developing into mountainous clouds of dust and earth and stones and trees. For some seconds the earth trembled and swayed. Then the guns and howitzers in their thousands spoke: the machine-gun barrage opened; and the infantry on a 10 mile front left the trenches and advanced behind the barrage against the enemy. The battle once launched, all was oblivion. No news came through for several hours: there was just he roar of the artillery - such a roar has never been heard before I went forward to study the results. German prisoners were already coming back wounded. I, as everybody else was doing, walked freely over the surface; past and over the old front line, where we have spent so many bitter months. How miserable and frail our wretched breastworks looked! When viewed - as for the first time I now saw them - from the parapet instead of from inside - the parapet only a sandbag thick in many places - what death-traps they seemed! Then over Noman's Land. As we stepped out there, my orderly, O'Rourke, remarked: 'This is the first time for two years that anyone has had the privilege of walking over this ground in daylight, sir.' We visited some of the mine craters made at the Zero hour, and huge indeed they are. Then we explored Petit Bois. and Wytschaete Wood - blown into space by our fire and non-existent - the scene of our raid of the night of June 4. We found the bodies of an officer and a man of ours missing since that night, which I have since had fetched out and buried among many of their comrades. I cannot hope to describe to you all the details of the battle on this scale. The outstanding feature, I think, was the astounding smallness of our casualties. The contrast in this respect with Loos and the Somme was most remarkable. Scarcely any dead were to be seen. The German dead had been mostly buried by the shell fire... as is always the way, we lost some of our best. A single shell - and a small one at that - knocked out twelve, killing three outright and wounding nine - two of the latter mortally. Among the victims of this shell were Major Stannus, commanding the 7th Leinsters, and his Adjutant (Acton), and Roche, the Brigade trench-mortar officer. I passed the last-named in my wanderings, lying by a dead private on the fire-step. He was, I think, one of the wittiest “raconteurs” I have ever met, and as brave and ready a soldier as I have ever seen. As Brigade trench-mortar officer he was a genius. In conversation he was remarkable. I lifted the sandbag which some one had thrown over his face. It was discoloured by the explosion of the shell that had killed him, but otherwise was quite untouched, and it wore the same slight smile that in life used to precede and follow his wonderful sallies. In peace-time he was a barrister. Willie Redmond also is dead. Aged fifty-four, he asked to be allowed to go over with his regiment. He should not have been there at all. His duties latterly were far from the fighting line. But, as I say, he asked and was allowed to go - on the condition that he came back directly the first objective was reached; and Fate has decreed that he should come back on a stretcher.... PS My men found a dead German machine-gunner chained to his gun. This is authentic. We have the gun, and the fact is vouched for by my men who took the gun, and is confirmed by their officer, who saw it. I do not understand the meaning of this: whether it was done under orders, or was a voluntary act on the part of the gunner to insure his sticking to the gun. If the latter, it is a thing to be admired greatly. As always seems to be my fate on these occasions I was reported seriously wounded!!

The following extract is from captured correspondence:

“Today the seventh alarm was given. Terrible drum fire was heard all during the night. A terrible firing has driven us under cover. To the right and left of me my friends are all drenched with blood. A drum fire which no one could ever describe. I pray the Lord will get me out of this sap. I swear to it I will be the next. While I am writing He still gives us power and loves us. My trousers and tunic and drenched in blood, all from my poor mates. I have prayed to God He might save me, not for my sake, but for my poor parents. I feel as if I could cry out, my thoughts are all the time with them. “The slaughtering takes place behind Messines, which place the English have taken. “I have already twelve months on the Western Front; have been through hard fighting, but never such slaughter.”

The first is where he describes the trench raid in which Willie was killed, the Battle of Messines and then going into what was formerly no man's land, and finding the body of WillieShaughnessy:

June 8, 1917 (Rossignol Wood) At 10.30 on the night of June 4

I launched my raid with 250 officers and men under Captain Tuite. The objective was the third line of the enemy's trenches, in Wytschaete Wood. Tuite was to advance behind a creeping artillery barrage and was given twelve minutes to reach his final

objective. The guns were then to form a 'box' barrage till the raiders got home again. He was allowed forty-five minutes in which to do the whole business. In such active times it was not possible to interfere with the ordinary work of the artillery for longer

than this. The raid was skilfully led and was entirely successful. These affairs sometimes seem to go off better when done on the spur of the moment than after long fussy preparation. About sixty Germans were killed and seven prisoners were

brought back, including an acting officer wearing the iron cross. The raiders returned in rags, their clothing torn to shreds by the enemy's wire, and today, after four more days of fighting, their clothes are in no better condition, as you can imagine. We

lost three officers - two killed and one blinded for life, I am afraid, by a bullet which penetrated his eye. There were about forty casualties among the men, mostly slight. One of the three principal shelters 'Harley House' - the one in which I had received

my shaking two days before, was however, flattened and Murphy - one of the regimental police who was on sentry duty - was killed... Poor Murphy had a photograph of his children in his pocket - a delightful-looking family. After midnight (June

5-6) we were relieved from the actual front line by the 6th Royal Irish Regiment.... During the night a lance-corporal of mine, who had been reported missing on the night of the raid - Fielding by name - was found in Noman's land, by another regiment

and brought in. He had been lying there twenty-four hours with six wounds! His finders were greatly impressed by his stoic behaviour. The 6th Connaught Rangers were to be broken up for the battle in order to provide “mopping up”

and carrying parties for the attacking battalions... I moved to my Battle Headquarters - a deep mined dug-out in Rossignol Wood, above which I am now writing this letter. The wood reeked of gas shells, to which the enemy further contributed during

the night. Yesterday morning (the great day) I got up and went out at three o’clock. The exact moment of the assault (known by us as “Zero”; by the French as “l’heure H”) which had been withheld by the Higher Command,

as is usual, till as late as possible, and had been disclosed to us as 3.10 am.

I climbed onto the bank of the communication trench, known as Rossignol Avenue, and waited. Dawn had not yet broken. The night was very still. Our artillery

was lobbing over an occasional shell; the enemy - oblivious of the doom descending upon him - was leisurely putting back gas shells, which burst in and around my wood with little dull pops, adding to the smell but doing no injury. The minute hand of my

watch crept on to the fatal moment. Then followed a “tableau” so sudden and dramatic that I cannot hope to describe it. Out of the silence and the darkness, along the front, twenty mines - some of them having waited two years and more for this

occasion - containing hundred of tons of high explosive, almost simultaneously, and with a roar to wake the dead, burst into the sky in great sheets of flame, developing into mountainous clouds of dust and earth and stones and trees. For some seconds

the earth trembled and swayed. Then the guns and howitzers in their thousands spoke: the machine-gun barrage opened; and the infantry on a 10 mile front left the trenches and advanced behind the barrage against the enemy. The battle once launched, all was

oblivion. No news came through for several hours: there was just he roar of the artillery - such a roar has never been heard before... I went forward to study the results. German prisoners were already coming back wounded. I, as everybody else was

doing, walked freely over the surface; past and over the old front line, where we have spent so many bitter months. How miserable and frail our wretched breastworks looked! When viewed - as for the first time I now saw them - from the parapet instead of from

inside - the parapet only a sandbag thick in many places - what death-traps they seemed!

Then over Noman's Land. As we stepped out there, my orderly, O'Rourke, remarked: 'This is the first time for two years that anyone has had the privilege

of walking over this ground in daylight, sir.' We visited some of the mine craters made at the Zero hour, and huge indeed they are. Then we explored Petit Bois. and Wytschaete Wood - blown into space by our fire and non-existent - the scene

of our raid of the night of June 4. We found the bodies of an officer and a man of ours missing since that night, which I have since had fetched out and buried among many of their comrades. I cannot hope to describe to you all the details of the

battle on this scale. The outstanding feature, I think, was the astounding smallness of our casualties. The contrast in this respect with Loos and the Somme was most remarkable. Scarcely any dead were to be seen. The German dead had been

mostly buried by the shell fire s is always the way, we lost some of our best. A single shell - and a small one at that - knocked out twelve, killing three outright and wounding nine - two of the latter mortally. Among the victims of this shell

were Major Stannus, commanding the 7th Leinsters, and his Adjutant (Acton), and Roche, the Brigade trench-mortar officer. I passed the last-named in my wanderings, lying by a dead private on the fire-step. He was, I think, one of the wittiest “raconteurs”

I have ever met, and as brave and ready a soldier as I have ever seen. As Brigade trench-mortar officer he was a genius. In conversation he was remarkable. I lifted the sandbag which some one had thrown over his face. It was discoloured by

the explosion of the shell that had killed him, but otherwise was quite untouched, and it wore the same slight smile that in life used to precede and follow his wonderful sallies. In peace-time he was a barrister. Willie Redmond also is dead. Aged fifty-four,

he asked to be allowed to go over with his regiment. He should not have been there at all. His duties latterly were far from the fighting line. But, as I say, he asked and was allowed to go - on the condition that he came back directly the first objective

was reached; and Fate has decreed that he should come back on a stretcher.... PS My men found a dead German machine-gunner chained to his gun. This is authentic. We have the gun, and the fact is vouched for by my men who took the gun, and is confirmed by their

officer, who saw it. I do not understand the meaning of this: whether it was done under orders, or was a voluntary act on the part of the gunner to insure his sticking to the gun. If the latter, it is a thing to be admired greatly. As always seems to be my

fate on these occasions I was reported seriously wounded!! The following extract is from captured correspondence: “Today the seventh alarm was given. Terrible drum fire was heard all during the night. A terrible firing has driven us under cover. To the

right and left of me my friends are all drenched with blood. A drum fire which no one could ever describe. I pray the Lord will get me out of this sap. I swear to it I will be the next. While I am writing He still gives us power and loves us. My trousers and

tunic and drenched in blood, all from my poor mates. I have prayed to God He might save me, not for my sake, but for my poor parents. I feel as if I could cry out, my thoughts are all the time with them. “The slaughtering takes place behind Messines,

which place the English have taken. “I have already twelve months on the Western Front; have been through hard fighting, but never such slaughter.”

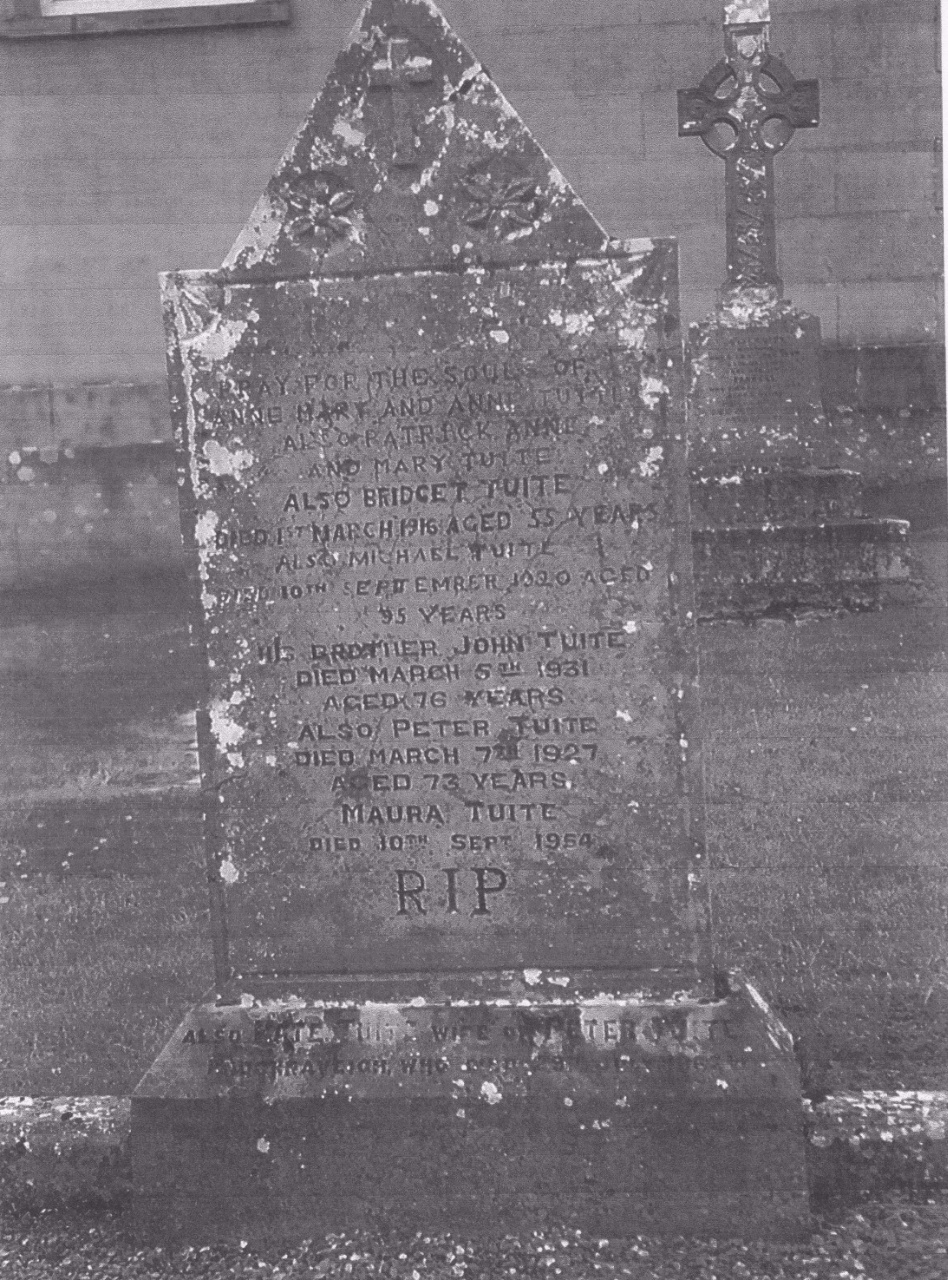

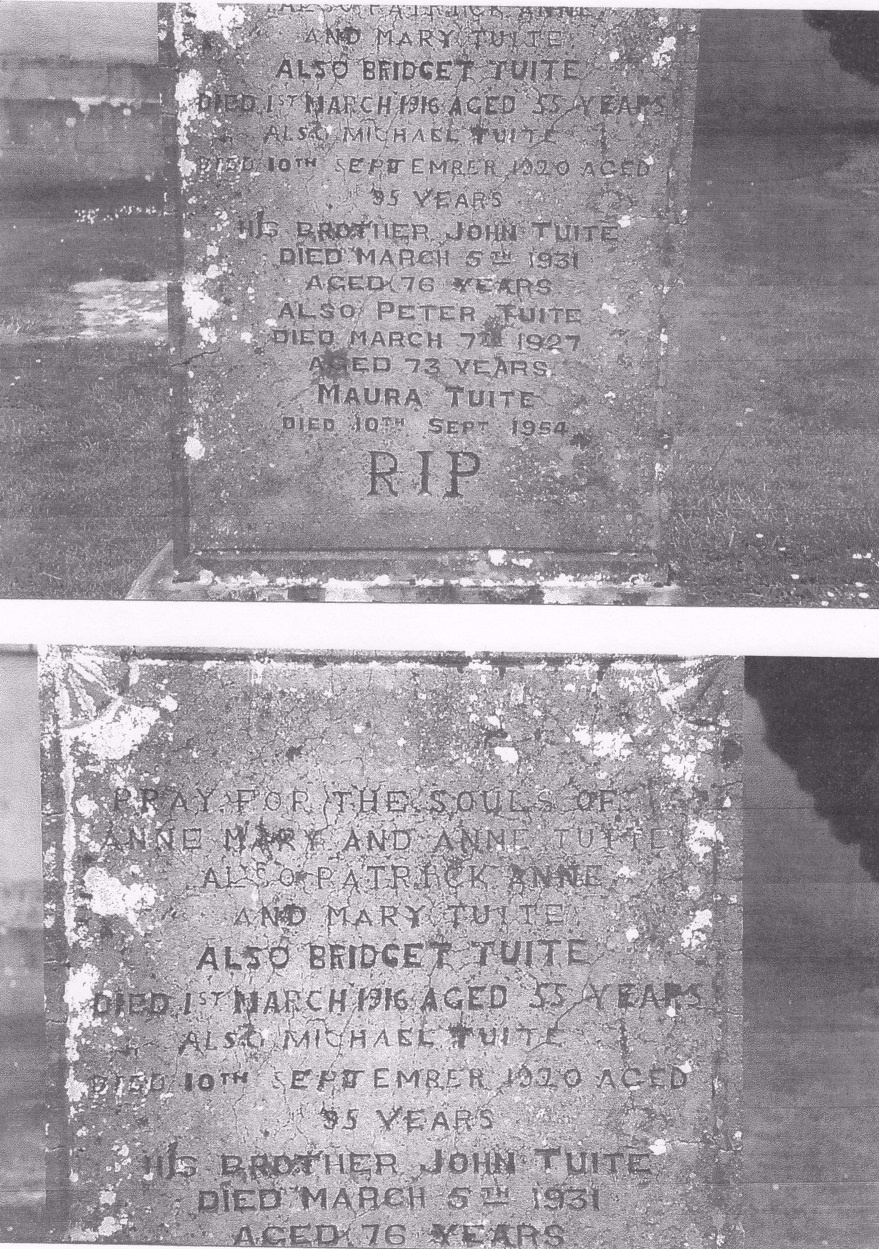

Gerard Tuite

Gerard Tuite

Gerard Tuite (born 1955) was a senior member of the Provisional Irish Republican Army. Upon his escape from Brixton prison during the Hunger Strike in the winter of 1980, he was declared the most wanted man in Britain. Following his capture, at 26 years of age, in the spring of 1982 he made Irish legal history by being the first Irish citizen charged with an offence committed in another country in a case which made international headlines. His prosecution in Ireland, for offences committed in Britain was a landmark one in international law.

Background

Gerry Tuite was born into a staunchly republican family in Mountnugent County Cavan, near the border with County Meath. He was one of the nine sons and two daughters born to Michael Tuite, a small farmer, and Jane Dermody. Their wedding day on 30 September 1942 made national headlines in Ireland when the wedding party was stormed by An Garda Síochána. According to the family the Garda shot a traditional musician called Finnegan in the leg and this was followed by a gun battle reminiscent of the Irish Civil War. The Garda were seeking the bride's brother, Patrick Dermody, who was the commanding officer of the IRA's Eastern Command and was on the run at the time. By the end of the battle Patrick Dermody lay dead, and a Detective Garda, M.J. Walsh, died later in hospital.

Gerry Tuite attended Kilnacrott Abbey secondary school in Ballyjamesduff in Cavan. In 1982 a fellow student remembered him thus: 'The only thing remarkable about him in those days was that he was unremarkable. He was a very inoffensive person- a nice quiet fellow.' He was viewed locally as the one member of the family most likely to stay out of politics, and was better known as a motorcycle enthusiast. In his late teens he became a merchant sailor. Little is known about him from this point until 1978.

IRA Activity

In that year, he was using the nom de guerre David Coyne and was believed to be a young businessman of German-Irish extraction when he met a nurse called Helen Griffiths at a party in London in the summer of 1978. Within a short time he had moved into Helen's flat in 144 Trafalgar Road, Greenwich. Helen's work allowed him much time in the flat on his own. Before the end of the year he was found guilty of possession of explosives with intent to endanger life. A sawn-off shotgun and Armalite rifle were also found at the flat. These and other items, including car keys and voice recordings, linked him to other bombings as well as the targeting of senior British Conservative and royal figures. According to J. Bowyer Bell, Tuite had also been involved in no less than eighteen bombing attacks in five British cities with Patrick Magee, the Brighton bomber, alone.

Tuite served his sentence in Brixton prison until 16 December 1980 when, in one of the most daring prison breakouts witnessed in Britain he escaped with two British inmates, one of whom was Jimmy Moody. Tuite and company escaped by tunnelling through walls of their cells in Brixton's top security remand wing and dropping into a yard where they used builders' planks and scaffolding piled up for repairs to scale the 15 ft perimeter wall. Coming during a major IRA hunger strike this proved to be an enormous boost to the morale of the movement, and consequently his escape was deemed to be a political emergency. Tuite's escape led the British police to immediately issue 16,500 posters of him under the heading "Terrorist Alert. This Man Must Be Caught." On 4 March 1982 Tuite was finally discovered, during a Special Branch raid on a flat in Drogheda Ireland. He received ten years in prison. In July 1982 he made Irish legal history when he became the first man sentenced in the Republic of Ireland for offences committed in the United Kingdom. He was sentenced by the Special Criminal Court to 10 years imprisonment for possessing explosives in London.

Tuite is today a businessman in the south Cavan and north Meath region.

Dan Tuite

The last native Irish speaker in south Monaghan, Dan Tuite, was from Kednaminsha: the very townland where Kavanagh went to school. He was still very much alive in the year the poet was writing, and he lingered for a decade thereafter, before expiring in 1957 and taking a regional dialect with him.

https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/an-irishman-s-diary-1.787790